Semiconductors

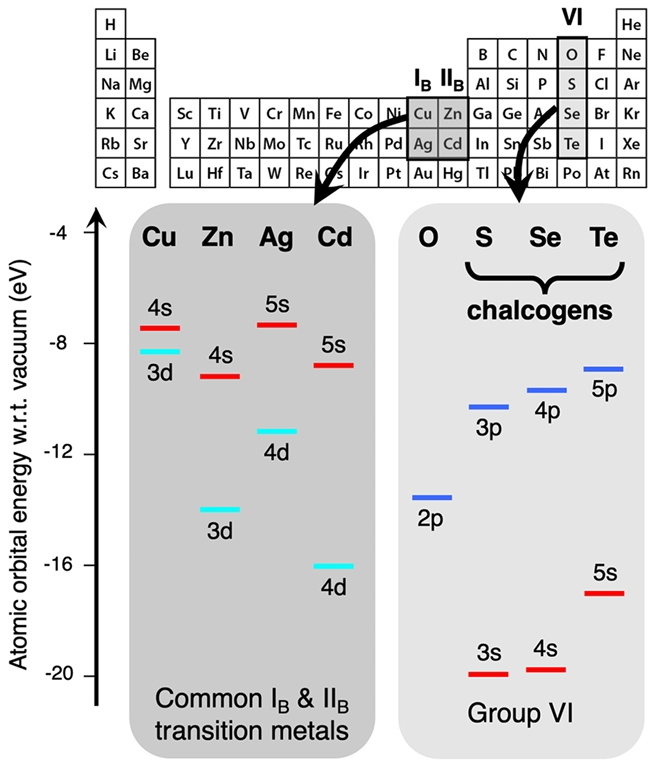

Semiconductors are the materials at the heart of many electronic devices. The elemental semiconductors are few, the only ones of any practical use being germanium (\(Ge\)) and silicon (\(Si\)) and only silicon is widely used nowadays. However, there are some compound semiconductors which find applications in light-emitting diodes, semiconductor lasers, microwave devices and other specialised areas. Most of these are based on elements from groups \(III\) and \(V\) of the periodic table and occasionally from groups \(II\) and \(VI\). These are known respectively as \(III-Y\) and \(II-VI\) compounds, examples being gallium arsenide (\(GaAs\)), gallium phosphide (\(GaP\)) and cadmium sulphide (\(CdS\)). The Semincondcting elements available in the Periodic Table are \(B\), \(C\), \(Si\), \(Ge\), \(As\), \(Se\), and \(Te\).

Electrons and holes

Semiconductors are only different from insulators because of conduction brought about by thermally generated charge carriers (intrinsic conduction) or by the addition of controlled amounts of impurities (extrinsic conduction), called dopants. In semiconductor devices only extrinsic conduction is desirable. The charge carriers are electrons and holes, which act just like positively-charged electrons. By adding the right kind of dopants it is possible to make semiconductor material which conducts either with electrons alone (\(n\)-type material) or with holes alone (\(p\)-type material). But first we must consider the ordinary processes of electrical conduction.

Electrical conductivity

The resistance, \(R\), of a bar of material of length, \(l\), and uniform cross-sectional area, \(A\), is

\[R = l/\sigma A\]

where \(\sigma\) is the electrical conductivity of the material. If \(l\) is in \(m\), \(A\) in \(m^{2}\) and \(R\) in \(\Omega\), then \(\sigma\) is in \(S/m\). The reciprocal of the conductivity is the resistivity, \(\rho\), which has units of \(\Omega m\).

The electrical conductivity of materials is found to vary over a very wide range - wider than any other material property. Materials came to be classified according to the behaviour and magnitude of their conductivities. Some, mainly metals and alloys, were found to be good conductors at room temperature (\(\rho\) ranging from about \(10^{-8}\) for silver to \(10^{-6}\) \(\Omega m\) for nichrome resistance wire), with a conductivity which decreased with increasing temperature and did not change much when the metal was impure. Other materials, mainly non-metals such as sulphur, polystyrene and silica, were found to have a very low conductivity at room temperature (\(\rho = 10^{10}\) to \(10^{16}\) \(\Omega m\)) which increased rather rapidly with temperature.

Again it was found that the purity of the material had relatively little effect on the conductivity or its temperature coefficient. Then there was another class of materials, such as germanium, silicon and silicon carbide, which had very variable conductivities (\(\rho = 10^{-6}\) to \(10^{2}\) \(\Omega m\)) and temperature coefficients that could be positive or negative and depended, it was eventually discovered, on the kind of impurities present, sometimes only in tiny amounts. Though these materials came to be called semiconductors, there is no fundamental difference between insulators and semiconductors: diamond is widely considered to be an insulator, and mostly it is, but semiconducting diamonds are known. Finally a fourth type of material was discovered (by Kammerlingh Onnes in 1911) that had no resistance at all below a critical temperature: it was a superconductor.